MONDAY, Feb. 13, 2017 (HealthDay News)

MONDAY, Feb. 13, 2017 (HealthDay News)

— People with low back pain should try drug-free remedies — from simple heat wraps to physical therapy — before resorting to medication, according to new treatment guidelines.

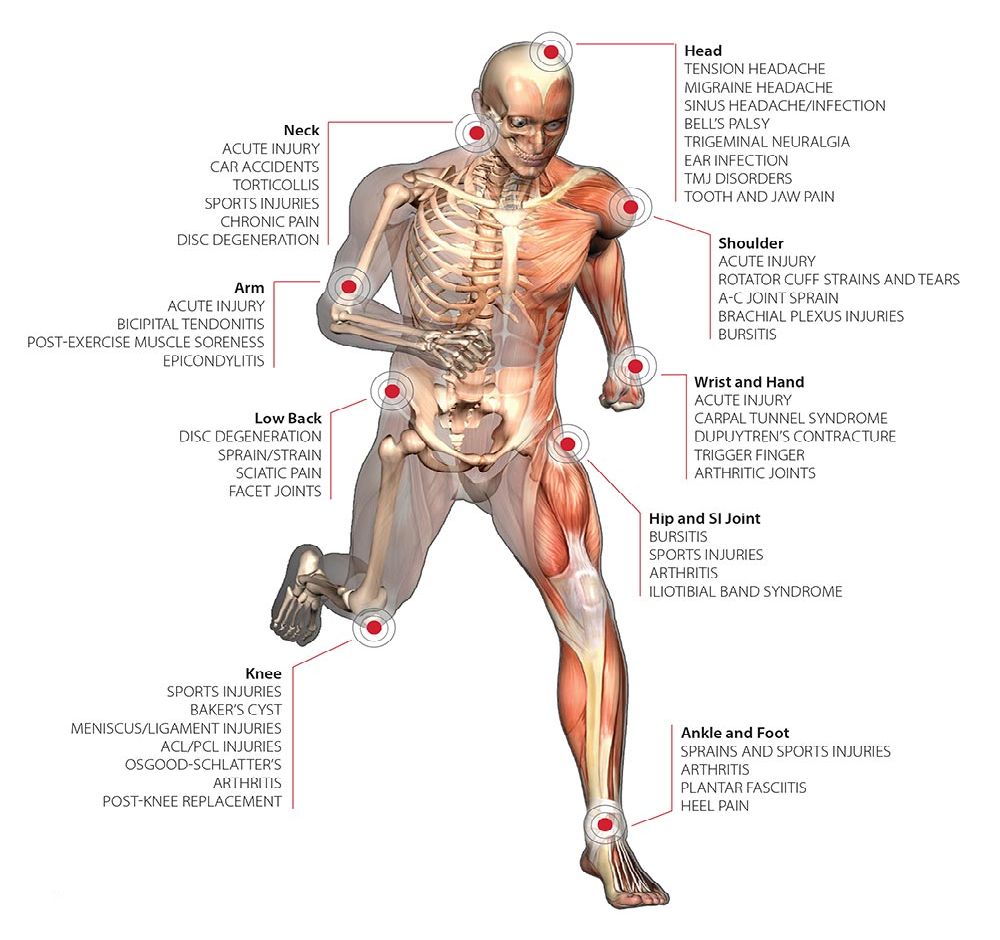

Low back pain is among the most common reasons that Americans visit the doctor, according to the American College of Physicians (ACP), which released the new guidelines on Monday.

The recommendations put more emphasis on nondrug therapies than previous ones have. They stress that powerful opioid painkillers — such as OxyContin and Vicodin — should be used only as a last resort in some cases of long-lasting back pain.

Another change: When medication is needed, acetaminophen (Tylenol) is no longer recommended. Recent research has shown it’s not effective for low back pain, said Dr. Nitin Damle, president of the ACP. The good news, according to Damle, is that most people with shorter-term “nonspecific” low back pain improve with simple measures like heat and changes in activity.

Nonspecific pain, Damle explained, is the kind where your back hurts and “you’re not sure what you did to it.”

He said that’s different from “radicular” back pain, which is caused by compression of a spinal nerve — from a herniated disc, for example. Typically, this problem has telltale symptoms like pain that radiates down the leg, or weakness or numbness in the leg.

In general, the ACP said, people with low back pain should first try nondrug options. For pain that has lasted fewer than 12 weeks, research suggests heat wraps, massage, acupuncture and spinal manipulation may ease pain and restore function to a moderate degree, according to the guidelines.

If the pain lasts more than 12 weeks, studies suggest some drug-free options can still be helpful, the ACP said.

Those include exercise therapy; acupuncture; “mind-body” therapies like yoga, tai chi, mindfulness-based stress reduction and guided relaxation techniques; and cognitive behavioral therapy.

When medication is used, the ACP advises starting with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve) — or possibly muscle relaxants.

“Only in rare circumstances should opioids be given,” Damle said. “And then only for a few days.” That’s partly because of the risks of opiate painkillers, he said, which include addiction and accidental overdose. Besides that, Damle added, there’s “little evidence” that opioids help people with low back pain.

The recommendations, published online Feb. 13 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, are based on a review of studies looking at what works — or doesn’t work — for various stages of low back pain.

In many cases, the ACP found, the therapies — drug or not — showed “small” to “moderate” benefits. When it came to radicular back pain, specifically, there was little evidence on what worked. But exercise therapy seemed to help. So, the guidelines say, nondrug options are the best first step.

For now, Atlas suggested people with mild back pain try to “de-medicalize” the problem and focus on simple self-care. For people with chronic pain, he said it’s important to be realistic about whatever therapy you try. “If you expect to have zero pain afterward, most of our therapies will disappoint,” Atlas said.

Click to read the entire article.